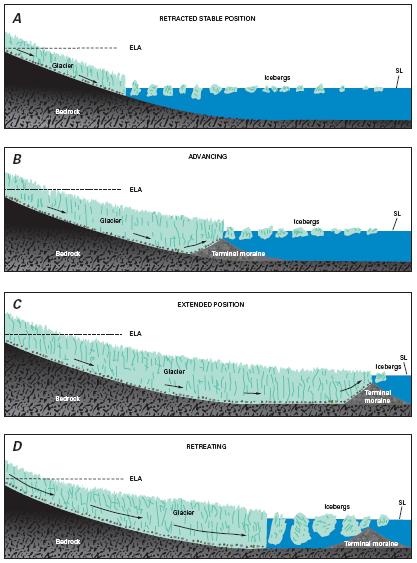

Basically, these are glaciers that flow out into the sea. Due to having no support from the ground, tidewater glaciers are unable to sustain their weight and as such pieces often break off into the water (known as calving), therefore creating icebergs. The majority of tidewater glaciers calve above the ice, thus creating huge splashes as the iceberg lands in the sea. Occasionally however, they calve underneath the water if the water is deep enough, with this often being identified by an iceberg shooting up into the air, like an armband would in a swimming pool.

Similarly to land glaciers, tidewater glaciers advance, pushing moraine in front of them, although this occurs under the water and is commonly known as a moraine shoal. This moraine shoal protects the glacier from deep tidal water although when the glacier begins to retreat from the moraine shoal, the deep water is unable to support it (as stated earlier) and as such calving will dramatically increase, further intensifying its rate of retreat until the glacier is small enough to once again support itself. At this point the calving will slow, and the tidewater glacier will again begin to advance, once again creating a new moraine shoal.

An example of a tidewater glacier is that of the Hubbard Glacier in Alaska. Alaskan tidewater glaciers often terminate vertically, with ice above the water rising to two to three hundred feet and stretching beneath the water up to a thousand feet.

The diagram below is a great one to really show how the process occurs and could easily be given to students to help them understand the process better (with perhaps the process being explained first as a drawing on the board).

No comments:

Post a Comment